Archive for the 'Reflections' category

NetFlix, Stream Movies for $57.99 per Month (Canada only)

November 6, 2010 So, we decided to give NetFlix a try a few weeks ago, just to get a feel for the experience; the platform of choice was our PS3 system. We were asking ourselves if this was a technology we would want to use to rent films that weren’t on our “must see” or “must own” list. I like to watch movies — a lot. After a long day at work, sometimes I am just mentally exhausted, which compels me to find sources of entertainment which are either completely different from what I working on during the day, or submit to a more passive form of recreation that doesn’t involve too much thought. I find movies a great way to relax and so I often partake in movie rentals at our local video store, sometimes as many as three or four times per week if I’m having a busy time at work. Most of the movies I rent tend to be fairly entertaining, but generally not a movie I would prefer to own, so the idea of streaming is very appealing to me since it eliminates the need to visit the mall. However, I prefer to think of the streaming business as a complement to existing movie distribution networks and not as a replacement.

So, we decided to give NetFlix a try a few weeks ago, just to get a feel for the experience; the platform of choice was our PS3 system. We were asking ourselves if this was a technology we would want to use to rent films that weren’t on our “must see” or “must own” list. I like to watch movies — a lot. After a long day at work, sometimes I am just mentally exhausted, which compels me to find sources of entertainment which are either completely different from what I working on during the day, or submit to a more passive form of recreation that doesn’t involve too much thought. I find movies a great way to relax and so I often partake in movie rentals at our local video store, sometimes as many as three or four times per week if I’m having a busy time at work. Most of the movies I rent tend to be fairly entertaining, but generally not a movie I would prefer to own, so the idea of streaming is very appealing to me since it eliminates the need to visit the mall. However, I prefer to think of the streaming business as a complement to existing movie distribution networks and not as a replacement.

I am living in an area now which is a tad on the remote side, so finding a decent video rental store is next to impossible, and the store I did find only provides a very small number of titles, most of which are still recorded as VHS cassettes. When my wife first talked to me about NetFlix, I must admit I was fairly reserved at the idea. I was mostly concerned about movie selection, but movie quality was also high on the list as well. After using it for a little less than a month, I must give the service 5 / 5 stars. I did see some minor quality problems in some movies, and the service had a bandwidth hiccup or two (probably not their fault), but overall I am very pleased with the video and audio quality and movie selection process. The NetFlix application on my PS3 is very easy to use with snappy response times and a rating system tuned to your personal tastes. The rating system does take time to learn what you like to watch, and it’s important to rate a film after you watch it.

The service costs $7.99 per month with the first month being free at the time of this writing. A standard-definition movie which runs for 2 hours consumes approximately 1.8 GB of data, while a high-definition movie running the same amount of time chews through approximately 3.0 GB of data. I don’t know what the consumer break-down is for Roger’s service plans, but one of their plans gives you a 60 GB transfer limit (upload + download) per month. Overage costs vary with your plan, and our plan costs us $2 for every GB over our 60 GB limit up to a maximum of $50 per month. We live in a 5 member house and four of us work in the technology sector, which means our tendency for data consumption is usually higher than most families, except those families with one or more tech savvy teenagers doing strange things in their basement. What this usually means is that we tend to consume more than half our available transfer limit just doing our day to day activities for work or recreation, which leaves less than 30 GB of wiggle room. That leaves us with the capacity for watching approximately 11 standard-definition movies, or  5 high-definition ones without getting charged extra. Since I prefer to watch some types of films in high-definition, my film roster is looking fairly small for an entire month, so naturally I’m going to enter into overage costs, rent more movies, or just do without.

I personally know a few families who use NetFlix mostly to provide entertainment for their children. I am wondering how often they run into overage costs since kids love to watch movies repeatedly, and does it save them money if they didn’t need to rent or buy those videos? For those types of users, it would be nice if NetFlix offered a download and record option so that the movies do not need to be repeatedly streamed. Those cached movies could have an expiration date based on the last time the movie was viewed (and not based on when it was downloaded), since NetFlix supports the policy of watching a movie as many times as you like. As usual, it would also behoove Rogers to offer more competitive Internet service plans (compared to the plans available in the USA), and for the CRTC to step out of the picture and stop meddling with what should be a privately run business sector. But, now I’m really dreaming.

Categories: Reflections

1 Comment »

Digital Download Dilemma

October 29, 2010I was reading an article on slashgamer.net that the PS4 was not going to support digital download only for games, and the writer was almost chastising the company for not embracing the future. Why, exactly, would we strive for this? I do not want an external server to hold the one and only back-up copy for the software I buy — if their service goes down for any reason (and they will go down permanently at some point), who do you think is going to be left holding the bag? Not to mention the Internet service provider problem. While a lot of us in North America have high speed connections, many of us do not have “unlimited” download (especially Canadians) contracts, and those which do have them, their download rates tend to be somewhat atrocious when you consider that the content you want to download is several gigabytes in size. In some cases, you will start your download today and maybe play your game tomorrow, assuming your connection stays healthy.

If you take the angle that there will be less packaging, therefore production costs will come down and the publishers will offer the game at a lower price, then you may want to think twice about that. Consider iTunes, for example, the music they offer is pretty much on par with the retail price of a physical compact disc, if you multiply the price you pay per song by an average number of songs per album (12-14). Less packaging may not translate into a cheaper price for the consumer, but it certainly does translate into larger margins for the publisher.

With the advent of collector’s editions becoming more popular, I was hoping that a trend towards better and more interesting packaging would be upon us. Think Baldur’s Gate, Space Quest, or the Ultima Games. Beautiful works of art and a real pleasure to own.

Categories: Reflections

2 Comments »

DOOM II: Let the obsession begin. Again.

December 23, 2008[Taken from the back of the box]

The wait is over. In your hot little hands, you hold the biggest, baddest Doom ever – DOOM II: Hell on Earth! This time, the entire forces of the netherworld have overrun Earth. To save her, you must descend into the stygian depths of Hell itself!

Battle mightier, nastier, deadlier demons and monsters. Use more powerful weapons. Survive more mind-blowing explosions and more of the bloodiest, fiercest, most awesome blastfest ever!

The 3-D modeling and texture bit-mapping technologies push the envelope out to the max. The graphics, animation, sound effects and gameplay are so virtually realistic, they’re unbelievable!

Play DOOM II solo, with two people over a modem, or with up to four players over a LAN (supporting IPX protocol). No matter which way you choose, get ready for adrenaline-pumping, action-packed excitement that’s sure to give your heart a real workout.

It must be tough to keep reading – what with your hands trembling in shear anticipation. So we’ll stop talking now to let you take this box to the counter.

DOOM II. It’s time to get obsessed again.

Categories: DOS, Reflections

No Comments »

Computer Virus Research

December 21, 2008As part of being a well-rounded programmer, I dabble in all sorts of technical things. One of my areas of interest is computer virus research. In the last thirty years, I have witnessed a large number of changes to this industry, and I find myself compelled to write a little bit about it today after reading about a couple of courses offered at the University of Calgary.

As it exists today, computer virus defense is wide collection of software programs and support networks which are offered to companies and users for the sole purpose of protecting their data from loss, damage, or theft from a myriad of small computer programs called computer viruses. These programs must have the ability to replicate (either a copy of themselves or an enhanced version) and which often carry a payload. The means by which a computer virus can replicate are complicated and often involve details of the operating system. In addition to preventing virus outbreaks from occurring, anti-virus software is also used to help prevent service outages and ensure a general level of stability. In other words, they are selling security or at least one form of security, since security in general is a very large net which cannot be cast by only one program. As an aside note, please be aware of the tools you are using for anti-virus protection. With some research and a little education, it’s often not necessary to purchase these programs in the first place.

I am currently reading Peter Szor’s book entitled, The Art of Computer Virus Research and Defense (ISBN-10: 0321304543). I am almost finished the text and I have found the book to be incredibly informative; filled with illustrations and summaries for all sorts of computer virus deployment scenarios, technical information about individual strains, and historical pieces of information as to how the programs evolved and mistakes made by both researchers and virus writers.

Even though I have the skills and the opportunities to do so, I have never written a computer virus for the purposes of deployment, nor do I ever wish to do so, but I can tell you that writing an original computer virus is challenging work; writing a simple virus is easy. Isolating, debugging, and analyzing the virus is also interesting work, albeit somewhat more tedious. Both jobs require similar skill sets, detailed knowledge of and low level access to a specific system.

I used to posit that the best virus writers would be the people who have taken it upon themselves to write the anti-virus software. After all, the best way to ensure the success of a business built on computer virus defense is to construct viruses that can be easily and quickly disarmed by your software. Much to the disappointment of conspiracy theorists, this is probably not the case, since fellow researchers would easily link a pre-mature inoculation with a future virus outbreak if it happened too often to be mere coincidence. However, if your business was based on quick and successful virus resolutions, then timely outbreaks followed by timely cures would seem to solidify the business model. Personally, I think anti-virus researchers are kept busy enough with “naturally” occurring strains to necessitate a manual jump start of the industry. Although that could change as users and technology platforms become more advanced, although the more probably route is the disappearance of the anti-virus industry; we live in a messy world and there may be opportunities for those wanting to leave their mark, even in the face of futuristic technology gambits.

Computer virus writers are plagued, somewhat ironically, by numerous problems with deploying their masterpiece. A computer virus can be written generically so that it can spread to a wider variety of hosts, or it can be written for a specific environment, which can include requirements on the hardware or software being used. Dependencies on software libraries, operating system components, hardware drivers and even specific types of hard-disks are all liabilities and advantages for a virus. They are liabilities because dependencies limit the scope of infection so the virus spreads more slowly, but at the same time, they often enable the virus to replicate, since the virus may be using known vulnerabilities or opportunities within these pieces to deliver the payload or as as means to allow for it to spread.

Virus research, writing, and defense is a fascinating topic. Unfortunately, I find the pomposity, and to some degree the absurdity, in various branches of the industry to be laughable and a little scary at times. In case you haven’t heard, the University of Calgary is offering a course on computer virus research. While I find this to be a refreshing take on education, my hopes are quickly dashed when I read the requirements and the Course Lab Layout (warning PDF monster). Do they think their students are secret agents working in a top secret laboratory? Of course they do, why else would there be security cameras installed in the room, and why do they restrict access to the course syllabus? Well, I’ve got news for the committee who approved the layout of the lab, and who probably approves the students who can attend the course: computer viruses are just pieces of software. That’s right, they’re just software. They don’t have artificially intelligent brains, they can’t get into your computer by the power lines, and they are quite a bit less complicated than your average word processor. This means that any programmer with the desire and a development environment can write a virus, trojan, or any other form of malware. They don’t need to take your course and they don’t need access to your Big Brother Lab.

The absurdity of protecting information which is already publicly available and has been for decades makes me want to laugh out loud and strangle someone at the same time. It’s rather disturbing and I really don’t like the idea of closing doors on knowledge, even if the attempt is futile. The University of Calgary’s computer science department should be ashamed at perpetuating such ignorance within a learning institution, and I am truly disappointed how bureaucratic such systems have become.

Update 12-29-20008:Â To respond to a verbal conversation I had with a couple of people: I understand why the university placed the security restrictions in the program; they want to validate the program and make it appear legitimate to the community and their peers. That’s fine, but at the same time, it must be acknowledged that the secret to mounting a successful defense against viral software and Internet based attacks is shared knowledge and open avenues for information. Understandably, this information will go both ways, but the virus writer will gain nothing they do not already possess (except the knowledge that we know what they are doing), while the general public may be a little more aware of the problem than they would be without this information.

Indeed, using viral kits and small customization programs can make viral programming easy for the layman or immature programmer, but we shouldn’t be locking away information about these techniques or programming practices simply because the result is something undesirable or easy to dispense. There are real opportunities to learn and disseminate this knowledge today, and the bigger the audience, the larger the opportunities for successful anti-viral software and general consumer awareness which will combine to create the most effective vaccine of all: knowledge.

Categories: Programming, Reflections

No Comments »

TheDRAW!

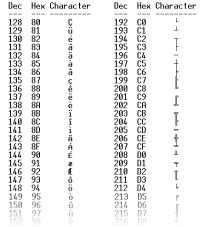

July 18, 2008There are two ways to render graphics in DOS. The first involves setting the desired graphics mode and then drawing pixels on the screen via the BIOS or writing directly to video memory (an interesting topic by itself); the second method involves staying in text mode and drawing pictures with the standard set of ASCII or IBM’s Extended ASCII characters (thanks to Telecom Corner for the chart).

While scripting batch files, you can also make use of ANSI escape sequences to control the cursor, display coloured or blinking text, etc. In case your interested, DOS requires an ANSI driver in order to translate these escape sequences. These escape sequences are non-intuitive and look something like this:

ESC[=5;7h

Ahh. Isn’t it cute? Many people have been discreetly killed for creating less offensive syntax than that. In addition to the regular set of ASCII characters which can be used in creative and artistic ways to produce a recognizable picture, using the set of extended ASCII characters provides an easy way to draw connected lines within the grid of displayable characters. When creating your picture keep in mind the screen size, since this is dependent on the video mode (some video modes can display more rows and columns).

TheDRAW was written by Ian E. Davis and was last released in October of 1993. It is a program which allows you to paint a picture or create an animation using these special characters and ANSI attributes. It’s not like painting individual pixels, you are limited by the set of characters available. However, this hasn’t stopped ASCII artists from creating fantastic content. The most stunning examples I found were on Bulletin Board Systems. They were often themed according to design of the on-line system. Using TheDRAW, these pictures could be exported as ANSI-compliant or ASCII text files, or as header files to be used in other programming languages. There are a number of small tools available for translating these files into other formats used by other languages.

TheDRAW was written by Ian E. Davis and was last released in October of 1993. It is a program which allows you to paint a picture or create an animation using these special characters and ANSI attributes. It’s not like painting individual pixels, you are limited by the set of characters available. However, this hasn’t stopped ASCII artists from creating fantastic content. The most stunning examples I found were on Bulletin Board Systems. They were often themed according to design of the on-line system. Using TheDRAW, these pictures could be exported as ANSI-compliant or ASCII text files, or as header files to be used in other programming languages. There are a number of small tools available for translating these files into other formats used by other languages.

TheDRAW package is bundled with a utility called TheGrab which can take an screen shot of a running program. It’s not your typical screen shot utility which takes snap shots of any graphics screen. This program works only for text mode screens and will output a file in ANSI, ASCII, COM, or TheDRAW format files. Be wary of using this memory resident utility under DOSBox 0.72 as it will crash and force you to end your session.

Last but not least, TheDRAW package is bundled with a utility for creating your own fonts to be used in TheDRAW paint program. This is without a doubt one of my favourite features and makes creating screens a breeze. There are many fonts available in the wide, wide world so have fun.

All of these features are thuroughly explained in the documentation and in-program help. Many of my programs took on a more professional and fun look because of this drawing tool; although I think I went overboard in some cases. I still find it the best tool available for doing this sort of work in DOS, although I’m sure many of you may prefer other software such as AcidDRAW.

Categories: DOS, Reflections, Software, Uncategorized

1 Comment »

AT Motherboards

June 10, 2008I’m wrestling with what to do with my AT motherboards. There are a number of problems when placing them in a system case which is either not an AT case or an ATX case with support for AT motherboards. I have the look of most cases as they tend to be that awful beige color. I’m also getting fed up with the size of the cases. They simply take up too much room in my home. I really want to keep the hardware because I like using the software, which ultimately makes the heavy, bulky boxes actually useful. I tried to make one of the cases look more modern and classy, but I’m dissatisfied with the quality of the paint I used (metallic paint which scratches easily, even after I applied a sealer). The modified case still doesn’t help much with the space issue.

I’m trying to run with the concept of an open system (no case) which is essentially mounted to a peg board. The boards could slide into slots on a rack which would save on space because there would be only one rack. Or I could create a rack capable of suspending multiple motherboards, which would then be mounted inside a cabinet. The cabinet could have a table top for the monitor, or the monitor could be mounted on the back of the cabinet. The hard part will be find the right cabinet… obviously, I’m still mulling it over.

Categories: Reflections, Retro

No Comments »

QBasic

December 5, 2007 When I mention QBasic to some people, they immediately think I’m talking about Quick BASIC. The two products, however, are a little different. They were both created by Microsoft but Quick BASIC is basically a super set of QBasic. QBasic has an interpreter and an editor built as one package; I hesitate to call it an IDE since your projects could only use one module at a time. It was also limited in the amount of memory available to the program and the amount of memory available to the editor. I experienced the latter problem only once while creating a game involving viruses and robots (I didn’t get around to naming it); the editor just started losing lines of code I had written and was behaving eradically. Eventually, I became frustrated and moved on to other and presumably smaller projects.

When I mention QBasic to some people, they immediately think I’m talking about Quick BASIC. The two products, however, are a little different. They were both created by Microsoft but Quick BASIC is basically a super set of QBasic. QBasic has an interpreter and an editor built as one package; I hesitate to call it an IDE since your projects could only use one module at a time. It was also limited in the amount of memory available to the program and the amount of memory available to the editor. I experienced the latter problem only once while creating a game involving viruses and robots (I didn’t get around to naming it); the editor just started losing lines of code I had written and was behaving eradically. Eventually, I became frustrated and moved on to other and presumably smaller projects.

QBasic made its first appearance with MS-DOS 5.0. It came with a few example programs and games. One of these games was called Nibble. I love this simple game, even to this day. It’s a little similar to games like Centipede, although the game itself is far too simple to make a reasonable comparison. The goal for each level is to gobble up the numbers that appear in random locations. Each time one of those numbers gets consumed, your “snake” grows a little longer. You have to avoid running into the walls of the level, which get more complicated as you progress, and you must not run into yourself. As you attain higher levels, your snake becomes faster and faster. This game was never synchronized with the system clock, so if you play the game on a machine made today, it would move around so quickly as to render the game unplayable.

I have often thought a game like Nibbles would make an excellent game to practice your porting skills on other platforms. It is sufficiently interesting to make the project worthwhile and could be adapted to play well using almost any input device. It could also be rendered using a simple text mode, just like the QBasic version, or you could enhance it in a graphics mode using imagery, vector graphics, etc.

QBasic also introduced the concept of functions and other forms of structured programming. GW-BASIC could only remember and execute your program if each line was prefixed by a number, or right away if you are using instructions in immediate mode. As you added and removed lines from your code, there were a couple of functions to reorder or renumber your line numbers when you ran out of room.

The concept of a function didn’t really exist in GW-BASIC; instead, it allowed you to jump to a particular line number using commands like GOTO or GOSUB. The latter was more like a function since you could jump to a specific region of code and then return from that function when the code had finished. GW-BASIC also supported one line functions which were handy for calculations. Although QBasic could still use line numbers, it encouraged the use of named labels for functions instead. Despite my work with Amiga’s BASIC, I still preferred the old way since I had been doing it for so long. It took me a while to adjust to the new program structure at first, so I purchased a new QBasic book after upgrading and essentially dove in head first.

Interrupts would become increasingly important for me in the future, but at this time I knew little about them. QBasic had no direct interface for handling interrupts, but it could handle interrupts used by the system’s timer:

ON TIMER(n) GOSUB MySubRoutine

Having no functionality to manipulate interrupts meant there were no functions to gather information about input devices like the mouse. Despite this seemingly major failing, all was not lost. While it could not handle input from the mouse directly, you could make use of a machine code sub-routine which could get the information you needed, like position and button states. You could use techniques like this to gather information from other devices.

QBasic also introduced me to one of the greatest time saving features ever created: the debugger. A debugger can be a separate program or feature within an IDE which allows you to trace through your program and examine variables and addressable data as the software executes. One of the core features of a debugger would be the ability to set a break-point at a specific addressable location that corresponds to a precise line within your source code. Before debugging, I was tracing through my program by hand and using PRINT commands to dump the contents of a variable. Even today, there are professional programmers who don’t use a debugger, either by choice or lack thereof, and choose to examine how there software operates by sending information to a log file or an output stream of some sort.

Categories: PC, Programming, Reflections

No Comments »

GW-BASIC

November 29, 2007 I first discovered this little gem while poking around on my Tandy 1000 RL computer back in 1991. Because I was familiar with various versions of BASIC already, I was able to fire it up and immediately begin writing fairly simple applications. However, there were differences to Atari’s version of BASIC, and no discernable way to figure that out without a book or some other documentation. I poked around on a few of my favourite Bulletin Board Systems (BBS) and found a small cache of programs written in GW-BASIC. I downloaded each of them, spending all of my download credits in the process. I poured over them line by line and found myself having more questions than answers.

I first discovered this little gem while poking around on my Tandy 1000 RL computer back in 1991. Because I was familiar with various versions of BASIC already, I was able to fire it up and immediately begin writing fairly simple applications. However, there were differences to Atari’s version of BASIC, and no discernable way to figure that out without a book or some other documentation. I poked around on a few of my favourite Bulletin Board Systems (BBS) and found a small cache of programs written in GW-BASIC. I downloaded each of them, spending all of my download credits in the process. I poured over them line by line and found myself having more questions than answers.

Many new programmers today expect there to be some sort of documentation available when they learn a new technology. It’s an expectation that has evolved over the years. Today, it would be practically unheard of if you couldn’t find some resource describing the software on the Internet, or some blurb in a book, or even bundled with the product. However, when I started looking for a book on GW-BASIC (version 3.23 to be exact), it was darn near impossible. The people I spoke with had no understanding of programming, let alone a specific language. The computer sections in the store were spartan compared to the sections you find in stores today. In fact, several years later, I still needed to special order the books I wanted through the book store; even today, I usually order my titles through Amazon since a store like Indigo usually doesn’t have them in stock.

I eventually wandered into a local computer store – I was attracted by a demo of Wing Commander II playing on one of their expensive new 486 machines, so I went in to ask them if they knew where I could get my hands on some material. I spoke with the owner and he seemed to recall seeing a book for BASIC in the back of the store. He left for a couple of minutes and returned with two books under his arm. One was for the exact version of GW-BASIC I was looking for and the other was a compatible book for MS-DOS. I was ecstatic and I nearly fainted when he gave them to me for free. I don’t remember what I said to the man that day, but I’m sure it wasn’t adequate.

I wrote so many programs in that environment. I think I still have a few of them today on floppy diskette. They were simple at first, like simple word games such as hangman. However, it wasn’t long before I discovered how to increase the resolution and colour depth and draw simple graphics. I had already written code for the Atari which made use of pixel plotting routines or simple geometric shapes. There were pre-canned routines the Atari provided for drawing shapes, along with a few parameters for style, colour, and shape. GW-BASIC was similar but provided several more commands and options. With a smaller font and a higher resolution, debugging within BASIC became more feasible. I still couldn’t scroll, but at least I could view a larger portion of the code on the screen.

Sound was also possible through the PLAY command, or if you were so inclined, through a custom routine written in assembly language which could be written to generate all sorts of sounds like noise or even speech. I had converted several songs using music sheets and converted them to their GW-BASIC equivalent. Not terribly exciting, but it did make for some creative demos which seemed to impress onlookers.

Some of the more interesting projects involved controlling external devices like printers. I must have programmed my software to use every conceivable option available through my Star NX 1000 II dot-matrix printer. I could instruct it to use standard type effects like bold and italics when printing text, but I could also program it to print graphical data like images and shapes. I even created printed graphics for the Mandel Brot set by rendering the fractal to my printer instead of the screen, one pixel at a time.

Perhaps the most interesting device was a robotic arm which was controlled through a series of commands dispatched through the parallel port. I didn’t have access to such a device at home but my school eventually purchased one, so one of the teachers decided to create a contest for students. Whoever could program the robotic arm first, would win a special prize. The task was to pick up a piece of chalk and draw a picture consisting of at least four shapes. It was a fun contest and I walked away with a pass which granted me as much lab time as I wanted.

Before I upgraded to a new machine and moved to a new version of MS-DOS, I was intimately familiar with every command in that book, even the more obscure commands like CHAIN and PCOPY. Although, the really obscure commands were still a mystery. I didn’t know you could actually write assembly language routines in GW-BASIC using DEF USR and USR commands until sometime later.

Categories: PC, Programming, Reflections, Software

No Comments »

Amiga OS

November 27, 2007 At around the same time I discovered DeskMate, the Amiga OS made its entry into the market as the aptly named operating system for the Amiga computer. Until recently, I had never owned an Amiga machine. I spent a fair amount of time with friends mucking around with various bits of software and hardware. One of my favourite combinations was the NewTek Video Toaster which was a powerful video editing software kit. You could do all sorts of video effects and overlays due to a technology called genlock. Genlock allowed you to synchronize different signals so that their sources become coincident, which made it possible for you to place blackout bar over your sister’s face just for kicks.It also sported several hardware and software features which I had never seen before. Real hardware multi-tasking was available on the Amiga 1000, but we mostly used the Amiga 500 which wasn’t as sophisticated in the same areas but provided terrific hardware for games. A friend of mine had a massive collection of software which were all archived in a custom-built diskette storage case made of wood and decaled with the Amiga logo. When we weren’t playing games and slogging through his massive collection of software, we were programming in Amiga BASIC or the occasional dip into the Lattice C compiler. I didn’t really understand the compiler since it was my first experience with a compiler, and it’s really difficult to learn a new programming technology when you have no means to experiment in your free time and no books available to read. At the time, I really wasn’t that interested anyway because I really connected with the structured BASIC available on the Amiga. It was a technology I could more readily understand because of my experience with Atari’s BASIC and Tandy’s GW-BASIC.

At around the same time I discovered DeskMate, the Amiga OS made its entry into the market as the aptly named operating system for the Amiga computer. Until recently, I had never owned an Amiga machine. I spent a fair amount of time with friends mucking around with various bits of software and hardware. One of my favourite combinations was the NewTek Video Toaster which was a powerful video editing software kit. You could do all sorts of video effects and overlays due to a technology called genlock. Genlock allowed you to synchronize different signals so that their sources become coincident, which made it possible for you to place blackout bar over your sister’s face just for kicks.It also sported several hardware and software features which I had never seen before. Real hardware multi-tasking was available on the Amiga 1000, but we mostly used the Amiga 500 which wasn’t as sophisticated in the same areas but provided terrific hardware for games. A friend of mine had a massive collection of software which were all archived in a custom-built diskette storage case made of wood and decaled with the Amiga logo. When we weren’t playing games and slogging through his massive collection of software, we were programming in Amiga BASIC or the occasional dip into the Lattice C compiler. I didn’t really understand the compiler since it was my first experience with a compiler, and it’s really difficult to learn a new programming technology when you have no means to experiment in your free time and no books available to read. At the time, I really wasn’t that interested anyway because I really connected with the structured BASIC available on the Amiga. It was a technology I could more readily understand because of my experience with Atari’s BASIC and Tandy’s GW-BASIC.

The Amiga OS made a strong impression on me as to what I was missing when I used a personal computer running DOS or Windows. There really wasn’t any comparison at the time. I remember feeling a bit underwhelmed whenever I switched my machine on after returning from a night of Amiga fun. However, after a few hours I was back into full swing. I’m not sure if I came to the realization that the machine I owned presented me with all sorts of different puzzles and tantalizing delights, but I do remember feeling like there was so much more to explore and learn. I believe that is what kept me from begging my folk’s for an Amiga every time I returned home. Although, I might have asked once or twice…

Categories: Amiga, Reflections, Software

No Comments »

Despite Tandy’s DeskMate application which tried to handle a number of disk and application related functions, MS-DOS (Microsoft Disk Operating System) was the actual operating system on which Deskmate needed to operate. I had experience with an earlier version of Microsoft’s DOS which I used at school; I believe the versions were 2.0 and 1.25. Unlike today where hard drives are common place and often taken for granted, the machines in the lab could only boot by way of 5 1/4″ floppy diskettes which contained the operating system. I believe the Tandy computer came with MS-DOS 3.42 and it was pre-installed on the hard drive. This was so much better than booting from a floppy, and I quickly assimilated as many commands as I could, since the school never gave me the time I wanted on the machine or the resources. Even with the aid of a text book, there were a few commands which took me a while to grasp, like COMMAND.COM or DEBUG.COM. My understanding of these wouldn’t completely solidify until I started programming in lower level languages like C and assembly language. I was also introduced to Microsoft’s shell scripts which they called Batch files. With the addition of extra software on the system, these scripts could actually become fairly sophisticated. Before I moved on to greener pastures and more flexible user interfaces, my system had sophisticated menus and launchers which helped my family out when they wanted to use the machine (it wasn’t often, but it did happen).

Despite Tandy’s DeskMate application which tried to handle a number of disk and application related functions, MS-DOS (Microsoft Disk Operating System) was the actual operating system on which Deskmate needed to operate. I had experience with an earlier version of Microsoft’s DOS which I used at school; I believe the versions were 2.0 and 1.25. Unlike today where hard drives are common place and often taken for granted, the machines in the lab could only boot by way of 5 1/4″ floppy diskettes which contained the operating system. I believe the Tandy computer came with MS-DOS 3.42 and it was pre-installed on the hard drive. This was so much better than booting from a floppy, and I quickly assimilated as many commands as I could, since the school never gave me the time I wanted on the machine or the resources. Even with the aid of a text book, there were a few commands which took me a while to grasp, like COMMAND.COM or DEBUG.COM. My understanding of these wouldn’t completely solidify until I started programming in lower level languages like C and assembly language. I was also introduced to Microsoft’s shell scripts which they called Batch files. With the addition of extra software on the system, these scripts could actually become fairly sophisticated. Before I moved on to greener pastures and more flexible user interfaces, my system had sophisticated menus and launchers which helped my family out when they wanted to use the machine (it wasn’t often, but it did happen).

Version 5 was a much more refined operating system and contained powerful commands and programs like QBasic. It also featured a memory manager which allowed software to access all of that wonderful new memory that you may have been fortunate enough to acquire. Although it was included in MS-DOS Version 4, I believe the DOSSHELL command’s popularity spiked in Version 5. This was a program which was intended as a graphical replacement to the dull COMMAND.COM shell. It introduced a feature called task swapping which allowed you to load more than one program but only run one of them at a time; unlike multitasking which appears to run more than one program at the same time. Also, DOSSHELL could not load more programs than your memory would allow since it did not have a paging mechanism. Naturally, all of these benefits conflicted with the new versions of Windows which did exactly the same thing only better, and was soon relegated to a supplemental disk in future releases before being dropped entirely.

Version 6 introduced the much feared DELTREE command. DELTREE was a command which could recursively remove directories and files; it was so feared because new or untrained users would presumably delete their entire operating system accidently. If this was indeed a problem, I think they should have modified the program to make it more difficult to accidently trash your operating system by adding extra prompts and warnings for example, since it is a very useful command in some circumstances. Despite its notoriety, it was a fairly simple command as far as software goes, and the void was soon filled by programmers who released new versions on the Internet which did exactly the same thing only better; I wrote a utility to replace it as well but mine displayed a user interface if you specified the right command option.

Categories: DOS, Reflections, Software

No Comments »